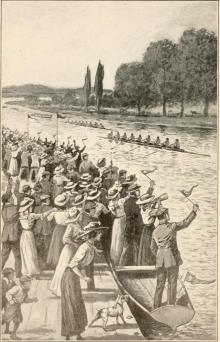

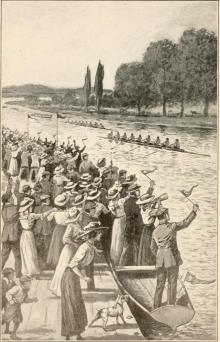

The Eight-Oared Victors: A Story of College Water Sports

The Eight-Oared Victors: A Story of College Water Sports For the Honor of Randall: A Story of College Athletics

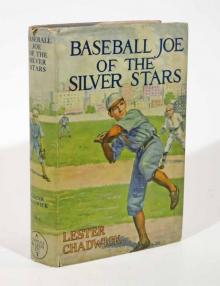

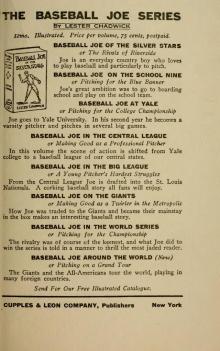

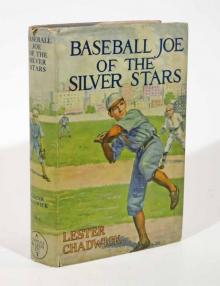

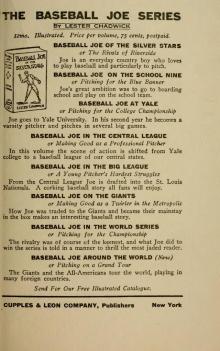

For the Honor of Randall: A Story of College Athletics Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; or, The Rivals of Riverside

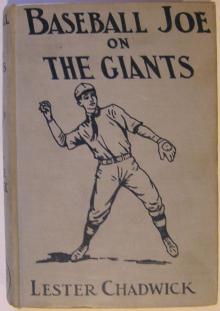

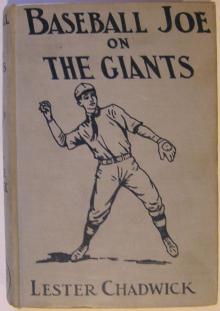

Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; or, The Rivals of Riverside Baseball Joe on the Giants; or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis

Baseball Joe on the Giants; or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis Baseball Joe on the School Nine; or, Pitching for the Blue Banner

Baseball Joe on the School Nine; or, Pitching for the Blue Banner The Winning Touchdown: A Story of College Football

The Winning Touchdown: A Story of College Football Baseball Joe, Home Run King; or, The Greatest Pitcher and Batter on Record

Baseball Joe, Home Run King; or, The Greatest Pitcher and Batter on Record Bolax, Imp or Angel—Which?

Bolax, Imp or Angel—Which? The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail

The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail Baseball Joe, Captain of the Team; or, Bitter Struggles on the Diamond

Baseball Joe, Captain of the Team; or, Bitter Struggles on the Diamond Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship

Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship Baseball Joe in the Big League; or, A Young Pitcher's Hardest Struggles

Baseball Joe in the Big League; or, A Young Pitcher's Hardest Struggles A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football

A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football Baseball Joe Around the World; or, Pitching on a Grand Tour

Baseball Joe Around the World; or, Pitching on a Grand Tour Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children

Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children The Eight-Oared Victors: A Story of College Water Sports

The Eight-Oared Victors: A Story of College Water Sports For the Honor of Randall: A Story of College Athletics

For the Honor of Randall: A Story of College Athletics Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; or, The Rivals of Riverside

Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; or, The Rivals of Riverside Baseball Joe on the Giants; or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis

Baseball Joe on the Giants; or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis Baseball Joe on the School Nine; or, Pitching for the Blue Banner

Baseball Joe on the School Nine; or, Pitching for the Blue Banner The Winning Touchdown: A Story of College Football

The Winning Touchdown: A Story of College Football Baseball Joe, Home Run King; or, The Greatest Pitcher and Batter on Record

Baseball Joe, Home Run King; or, The Greatest Pitcher and Batter on Record Bolax, Imp or Angel—Which?

Bolax, Imp or Angel—Which? The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail

The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail Baseball Joe, Captain of the Team; or, Bitter Struggles on the Diamond

Baseball Joe, Captain of the Team; or, Bitter Struggles on the Diamond Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship

Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship Baseball Joe in the Big League; or, A Young Pitcher's Hardest Struggles

Baseball Joe in the Big League; or, A Young Pitcher's Hardest Struggles A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football

A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football Baseball Joe Around the World; or, Pitching on a Grand Tour

Baseball Joe Around the World; or, Pitching on a Grand Tour Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children

Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children