- Home

- Lester Chadwick

Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children Page 8

Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children Read online

Page 8

THE MERRY-GO-ROUND

The Basket Woman was washing for the homesteader's wife at the spring,and Alan, by this time very good friends with her, was pulling upsagebrush for the fire, when the coyote came by. It was a clear, widemorning, warm and sweet, with gusty flaws of cooler air moving down fromPine Mountain. There was a lake of purple lupins in the swale, and thelast faint flush of wild almonds burning on the slope. The grapevines atthe spring were full of bloom and tender leaf. Eastward, above the hightilted mesa under the open sky, the buzzards were making amerry-go-round. That was the way Alan always thought of theirperformance when he saw them circling slantwise under the sun. Round andround they went, now so low that he could see how the shabby wingfeathers frayed out at the edges, now so high that they became merespecks against the sky.

"What makes them go round and round?" asked Alan of the mahala.

"They go about to wait for their dinner, but the table is not yetspread," said she. The Basket Woman did not use quite such good English;but though Alan understood her broken talk, you probably would not. Thelittle boy could not imagine, though he tried, what a buzzard's dinnermight be like. The high mesa, with the water of mirage rolling over it,was a kind of enchanted land to him where almost anything might happen.He would lie contentedly for hours with his head pillowed on thehillocks of blown sand about the roots of the sage, and look up at themerry-go-round. He noticed that, although others joined them from theinvisible upper sky, none ever seemed to go away, but hung and circledand faded into the thin blue deeps of air. Often he saw them settleflockwise below the rim of the mesa and beyond his sight, wonderinggreatly what they might be about.

The morning at the spring he watched them in the intervals of tendingthe sagebrush fire, and then it was that the coyote came by, going inthat direction. His head was cocked to one side, and he seemed to watchthe merry-go-round out of the corner of his eye as he went.

Alan thought the little gray beast had not seen them at the spring, butin that he was mistaken. A quarter of an hour before, as he came up outof the gully that hid his lair, the coyote had sighted the boy and theBasket Woman and made sure in his own mind that they had no gun. So, asit lay in his way, he came quite close to them; opposite the spring hepaused a moment with one foot lifted, and eyed them with a wise andsecret look. He went on toward the mesa, stopped again, looked back andthen up at the whirling buzzards, and went on again.

"Where does that one go?" asked Alan.

"Eh," said the Basket Woman, "he goes also to the dinner. It is goodeating they have out there on the mesa together."

Alan looked after him, and the coyote paused and looked back over hisshoulder as one who expects to be followed, and quite suddenly it cameinto the boy's mind to go up on the mesa and see what it was all about.The Basket Woman was bent above her tubs and did not see him go; whenshe missed him she supposed he had gone back to the house. Alan trottedon after the coyote until he lost him in a sunken place full of bouldersand black sage; but he had been headed still toward that spot abovewhich the black wings beat dizzily, and that way Alan went, climbing bythe help of stout shrubs to the mesa, which here fell off steeply to thevalley, and then on until he saw his coyote or another one, goingsteadily toward the merry-go-round.

The mesa was very warm, and swam in misty blueness although the day wasclear. Dim shapes of mountains stood up on the far edge, and near by aprocession of lonely, low hills rounded like the backs of dolphinsappearing out of the sea. Stubby shrubs as tall as Alan's shouldercovered the mesa sparingly, and in wide spaces there were beds ofyellow-flowered prickly-pear; singly and far stood up tall stems ofwhite-belled yucca, called in that country Candles of Our Lord. Alancould not follow the coyote close among the scrub, but dropped presentlyinto a cattle trail that ran toward the place where he supposed thecoyote's dinner must be, and so trudged on in it while the sun wheeledhigh in the heavens and the whole air of the mesa quivered with theheat.

It is certain that in his wanderings Alan must have traveled that dayand the next as much as twenty miles from the spring, though he mighteasily have been lost in less time, for his head hardly came above thetops of the scrub, and there were no landmarks to guide by, other thanthe low hills which seemed to alter nothing whichever way one looked atthem. As for the buzzards, they rose higher and higher into the dim,quivering air. Alan began to be thirsty, next tired, and then hungry. Hetried to turn toward home, but got no nearer, and finally understoodthat he might be lost, so he ran about wildly for a time, which madematters no better. He began to cry and to run eagerly at the same timeuntil, blind and breathless, he would fall and lie sobbing, and wishthat he might see his mother or the Basket Woman come walking across themesa with her basket on her back. By this time it was hot and close andhe had come where the scant-leaved shrubs were far between, and withheat and running the tears were dried out of him. He sobbed in hisbreath and his lips were cracked and dry. It fell cooler as night drewon, but he grew sick with hunger, and shuddered with the fear ofdarkness. Far off across the mesa the coyotes began to howl.

Down in the homesteader's cabin nobody slept that night. When they firstmissed Alan, which was at noon, no one had the least idea where he was.His mother had supposed him at the spring, and the Basket Woman thoughthe had gone to his mother. It was all open ground about the cabin fromthe mesa and the foot of the hills, and below it toward the valley barestretches of moon-white sands.

The homesteader thought that the boy might have gone to the campoodie;but there they found he had not been, and none of the Indians had seenhim; but by three of the clock they were all out beating about thespring to pick up the light trail of his feet, and there they were whenthe quick dark came on and stopped them.

By the earliest light of the next morning the Basket Woman, who wasreally very fond of him, had come out of her hut to ask for news, butwhen she had looked up to the sky for a token of what the day was to be,she saw the buzzards come slantwise out of space and begin themerry-go-round. All at once she remembered Alan's question of the daybefore, and though she could not reasonably expect any one to take anynotice of it, an idea came into her head and a gleam into her beadyeyes. She caught her pony from the corral, riding him astride as Indianwomen ride, with the wicker water bottle slung across her shoulder and aparcel of food hid in her bosom. She went up the mesa rim toward thespot where the buzzards swung circling in the sky.

When Alan awoke that morning under the creosote bush, he thought hemust have come nearly to the place he had meant to find the day before.There was the coyote skulking out in the cactus scrub, and the buzzardswheeling low and large. It was a hot, smoky morning, the soil was all ofcoarse gravel, loose and white. Over to the right of him lay a stillblue pool, and a broad river flowed into it in soft billows withoutsound. The coyote went toward it, looking back over his shoulder, andAllan followed, for his tongue was swollen in his mouth with thirst. Thelittle boy was quite clear in his mind; he knew that he was lost, thathe was very hungry, and that it was necessary to find his father andmother very soon. As he had come toward the mountains the day before, hethought that he should start directly away from them. He thought hecould not be far from the campoodie, for it came to him dimly that hehad heard the Indians singing the coyote song in the night, but he meantto have a drink in the soft still billows of the stream. A little aheadof him the coyote seemed to have gone into it, his head just clearedthe surface, and the water heaved to the movements of his shoulders. Butsomehow Alan got no nearer to it. The stream seemed to loop and curveaway from him, and presently he saw the lake behind him and could notthink how that could be, for he did not understand that it was a lakeand river of mirage. He saw the trees stand up on its borders, andfancied that the air which came from it was moist and cool. Always thecoyote went before and showed him the way, and at last he lifted up hislong thin muzzle and made a doleful cry. Mostly it seemed to Alan thatthe coyotes howled like dogs, but a little crazily; now it appeared thatthis one spoke in words that he could understand. When he

told hismother of it afterwards, she said it was only the fever of his thirstand fatigue, but the Basket Woman believed him.

"Ho, ho!" cried the coyote, "come, come, my brothers, to the hunting!Come!"

A great black shadow of wings fell over them and a voice cried huskily,"What of the quarry?"

"The quarry is close at hand," said the coyote, and Alan wondereddizzily what they might be talking about. He could not look up, for hiseyes were nearly blinded by the light that beat up from the sand, but hesaw wing shadows thickening on the ground.

"Where do you go now?" cried the voice in the upper air.

"Round and about to the false water until he is very weary," said thecoyote; and it seemed to Alan that he must follow where the gray dogwent in a maze of moving shadows. He trembled and fell from weakness agreat many times and lay with his face in the shelter of the pricklebushes, but always he got up and went on again.

"Have a care," cried the voice in the air, "here comes one of his ownkind."

"What and where?" said the coyote.

"It is a brown one riding on a horse; she comes up from the gully of bigrocks."

"Does she follow a trail?" panted the coyote.

"She follows no trail, but rides fast in this direction," croaked thevoice, but Alan took no interest in it. He did not know that it was theBasket Woman coming to rescue him. He thought of the merry-go-round, forhe saw that he had come back to the creosote bush where he had spent thenight, and he thought the earth had come round with him, for it rockedand reeled as he went. His tongue hung out of his mouth and his lipscracked and bled, his feet were blistered and aching from the sharprocks, the hot sands, and cactus thorns. Round and round with him wentscrub and sand, on one side the shadow of black wings, and on the otherthe smooth flow of mirage water which he might never reach. Through itall he could hear the soft _biff, biff_ of the broad wings and the long,hungry, whining howl that seemed to detach itself from any throat andcome upon him from all quarters of the quivering air. Dizzily went themerry-go-round, and now it seemed that the false water swung nearer,that it went around with him, that it bore him up, for he no longer feltthe earth under him, that it buoyed and floated him far out from theplace where he had been, that it grew deliciously cool at last, that itlaved his face and flowed in his parched throat; and at last he openedhis eyes and found the Basket Woman trickling water in his mouth fromher wicker water bottle. It was noon of his second day from home whenshe found him on Cactus Flat, by going straight to the point where shesaw the black wings hanging in the air. She laid him on the horse beforeher and dripped water in his mouth and coaxed and called to him, butnever left off riding nor halted until she came up with others of thesearch party who had followed up by the place where Alan had climbed tothe mesa, and followed slowly by a faint trail. But to Alan it was allas if he had dreamed that the Basket Woman had brought him as beforefrom the valley of Corn Water. The first that he realized was that hisfather had him, and that his mother was crying and kissing the BasketWoman. It was several days before he was able to be about again, andthen only under promise that he would go no farther than the spring.The first thing he saw when he looked up was the buzzards high up overthe mesa making a merry-go-round in the clear blue, and it was then heremembered that he had not yet found out what it was all about.

The Eight-Oared Victors: A Story of College Water Sports

The Eight-Oared Victors: A Story of College Water Sports For the Honor of Randall: A Story of College Athletics

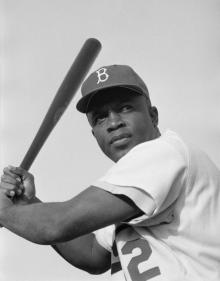

For the Honor of Randall: A Story of College Athletics Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; or, The Rivals of Riverside

Baseball Joe of the Silver Stars; or, The Rivals of Riverside Baseball Joe on the Giants; or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis

Baseball Joe on the Giants; or, Making Good as a Ball Twirler in the Metropolis Baseball Joe on the School Nine; or, Pitching for the Blue Banner

Baseball Joe on the School Nine; or, Pitching for the Blue Banner The Winning Touchdown: A Story of College Football

The Winning Touchdown: A Story of College Football Baseball Joe, Home Run King; or, The Greatest Pitcher and Batter on Record

Baseball Joe, Home Run King; or, The Greatest Pitcher and Batter on Record Bolax, Imp or Angel—Which?

Bolax, Imp or Angel—Which? The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail

The Broncho Rider Boys on the Wyoming Trail Baseball Joe, Captain of the Team; or, Bitter Struggles on the Diamond

Baseball Joe, Captain of the Team; or, Bitter Struggles on the Diamond Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship

Baseball Joe in the World Series; or, Pitching for the Championship Baseball Joe in the Big League; or, A Young Pitcher's Hardest Struggles

Baseball Joe in the Big League; or, A Young Pitcher's Hardest Struggles A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football

A Quarter-Back's Pluck: A Story of College Football Baseball Joe Around the World; or, Pitching on a Grand Tour

Baseball Joe Around the World; or, Pitching on a Grand Tour Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children

Basket Woman: A Book of Indian Tales for Children